Normally I wouldn’t have looked twice at a book like Essentialism: The Disciplined Pursuit of Less by Greg McKeown. I’ve read a number of books on time management, achieving goals, etc., so I wasn’t looking for one more.

But I listened to an interview with the author as part of one writer’s group’s attempts to draw in new members. And though I decided not to join the writer’s group, I appreciated much that Greg had to say.

These days, we’re all beset by having more opportunities and responsibilities than we can keep up with. Plus other people can pile their agendas on to us. We spend much of our time “busy but not productive.”

The way of the Essentialist means living by design, not by default. Instead of making choices reactively, the Essentialist deliberately distinguishes the vital few from the trivial many, eliminates the nonessentials, and then removes obstacles so the essential things have clear, smooth passage. In other words, Essentialism is a disciplined, systematic approach for determining where our highest point of contribution lies, then making execution of those things almost effortless (p. 7).

Lest that sound cold and heartless, one of our essentials is our loved ones. One of the catalysts to McKeown’s journey towards essentialism was when he was pressured to be at a meeting with a client just hours after his daughter was born. He was told the client would respect him for his sacrifice of being there. But the client didn’t, and the meeting in the end turned out to be pretty worthless.

Trade-offs are going to happen as we learn we can’t do everything. It’s better to decide ahead of time what’s really most important and spend our energy there, even when that means saying no to other things, even good things.

Part 1 of McKeown’s book focuses on essence: to do what’s essential, we first have to figure out what’s essential according to our goals and values. We have to determine what’s non-negotiable and what’s a trade-off.

Part 2 is Explore: the “perks of being unavailable,” the necessity of sleep and even play.

Part 3 is Eliminate: to say yes to some things, we have to say no to others. Part 3 explores principles and methods for eliminating the nonessential.

Part 4 is Execute: protecting our essential goals by implementing buffer zones, starting small and celebrating small wins, the helpfulness of routines to eliminate unnecessary decisions, flow and focus.

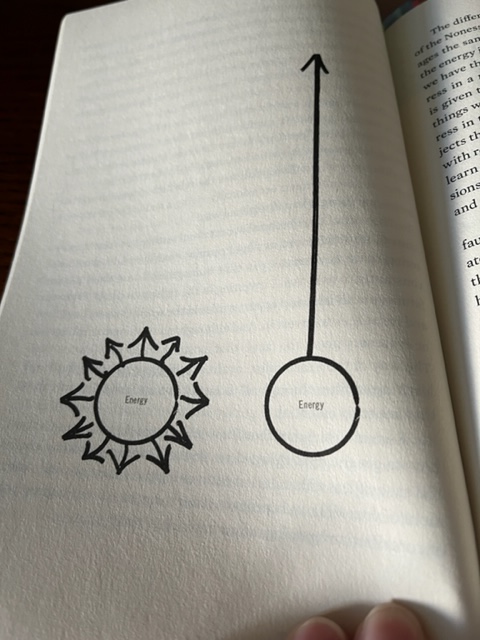

Sprinkled throughout the book are simple but very effective illustrations. This one, for example, shows “the unfulfilling experience of making a millimeter of progress in a million directions” vs. “investing in fewer things” to “have the satisfying experience of making significant progress in the things that matter most” (pp. 6-7).

Here are a few of the other quotes that stood out to me:

For capable people who are already working hard, are there limits to the value of hard work? Is there a point at which doing more does not produce more? Is there a point at which doing less (but thinking more) will actually produce better outcomes? (p. 42).

We need to be as strategic with ourselves as we are with our careers and our businesses. We need to pace ourselves, nurture ourselves, and give ourselves fuel to explore, thrive, and perform (p. 94).

An essential intent, on the other hand, is both inspirational and concrete, both meaningful and measurable. Done right, an essential intent is one decision that settles one thousand later decisions. It’s like deciding you’re going to become a doctor instead of a lawyer. One strategic choice eliminates a universe of other options and maps a course for the next five, ten, or even twenty years of your life. Once the big decision is made, all subsequent decisions come into better focus (p. 126).

The way of the Essentialist isn’t just about success; it’s about living a life of meaning and purpose. When we look back on our careers and our lives, would we rather see a long laundry list of “accomplishments” that don’t really matter or just a few major accomplishments that have real meaning and significance? (p. 230).

McKeown includes multiple examples from businesses and institutions. Just about the time I wished he brought some of his illustrations and principles down to a person level, he did.

One problem that he didn’t discuss, though, is when you can’t say no to obligations that seem meaningless. He says several times that saying no to the unnecessary meeting or obligation actually garners respect instead of resentment. But that’s not always the case. And you can’t always say no if your boss requires something that you think is a waste of time.

And you have to be careful that your time-savers don’t become an imposition on someone else. For instance, he mentions someone who skipped a regular hour-long meeting at work to get his own work done, then got a ten-minute summary from a coworker, thus saving himself forty minutes. But he doesn’t note that this guy was putting an unnecessary drain on his coworker’s time. If I had been the coworker, I would have been tempted to say, “If you want to know what happens at the meetings, you need to be there. I have too much to do to recap them for you every week.”

But those instances are minor. Most of what the author had to say was very good.

This isn’t a Christian book, and the author recommends a wide range of resources that I wouldn’t always agree with.

But overall, McKeown gave me much to chew on.

Similiar concepts are found in Hebrews 12:1 and 1 Corinthians 9:24-27. I might get this book.

At first I thought the title was “Existentialism.” 🙂

😀

He has some great points. And I think I’ll take the author’s advice and not read the book, but just enjoy your recap! 😉

He has so much more in there than I could share here. 🙂

I like this — minimalism for life rather than just for stuff! The illustrations help grasp the topics really well.

I kind of like essentialism (a word I assume he made up) better than minimalism—the latter always seemed a little spartan to me.

Sometimes it takes a secular author to cement the wisdom of God in our hearts!

Pingback: September Reflections | Stray Thoughts

Pingback: Reading Challenge Wrap-Ups | Stray Thoughts

Pingback: Books Read in 2022 | Stray Thoughts