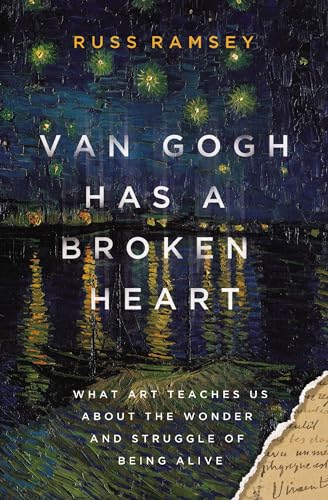

Van Gogh Has a Broken Heart: What Art Teaches Us About the Wonder and Struggle of Being Alive by Russ Ramsey is similar to his earlier book, Rembrandt Is In the Wind. Each draws observations from art and artists. This second book explores the theme of suffering and the beauty and grace that comes from it.

Art shows us back to ourselves, and the best art doesn’t flinch or look away. Rather, it acknowledges the complexity of struggles like poverty, weariness, and grief while defiantly holding forth beauty—reminding us that beauty is both scarce and everywhere we look (p. 4).

Beauty pulls us upward toward something that calls for some measure of discretion, something to be treated with dignity and care, something sacred. What does it pull us toward? The truth that we were made to exist in the presence of glory (p. 5).

All art comes from somewhere. It comes from someone who is in the process of living the one life they’ve been given. The more we can understand the specifics of their individual experience, the more we will understand why they created what they did and why the world has responded to it in the way we have (p. 12).

Ramsey says sad stories are universal, and they can provide fellowship in whatever we’re going through as well as empathy for others. They help us wrestle with the evil and brokenness in the world. “They remind us not just that this world can wound us, but that wounds can heal. They remind us to hope” (p. 10). They show us that beauty can come from brokenness.

That’s not to say all art comes through suffering. I think it was in my Music Appreciation class in college I heard a comparison of Beethoven and Haydn and how their lives shaped their music. Beethoven had a difficult father, health issues, and started experiencing hearing loss before he was thirty. Haydn had struggles, but by his thirties he had a steady job as the music director for a prince. A lot of his work is light, clever, even playful, while Beethoven’s is rich in emotional depth.

There are ten chapters in Ramsey’s book. One tells the story of how the Mona Lisa was stolen and recovered, Pablo Picasso was a suspect, and the painting became a lot more famous after the theft. Another contrasts Rembrandt’s Simeon’s Song of Praise, which is very detailed and elaborate, painted early in his career, with Simeon in the Temple, painted late in his career and found after his death. They cover the same incident in the Bible, but the latter is simple and focuses on Simeon’s emotion.

When I look at the old painter’s reimagining of the scene, to my eye he doesn’t seem to want to show us the spectacle of the temple when Simeon held Jesus, or what he can do with it as a painter. After a life filled with suffering and sorrow, he just seems to want to hold Jesus (p. 51).

Artemisia Gentileschi was a painter I’d never heard of. Ramsey describes the difficulty of a woman in this field as well as an artist working “for hire”–not painting scenes she loved for the pure pleasure of it, but taking commissions of what others wanted to see painted. He points out that “she’s not a girl-power feminism icon. She’s an icon in the sense that she’s an example of a woman who’s navigating a world that’s not built for her” (p. 66). “We must be careful not to romanticize her work to make it fit our own cultural moment. It is one thing to draw conclusions about the impact of her art over time, and quite another to assign intent to her body of work that may not represent how she thought about it (p. 66). I wish people who try to bring modern-day sensibilities into other people’s history would realize “If we come to an artist like Artemisia with a narrative already in mind and insert her into it, we dishonor her actual experience” (p. 67).

Joseph Turner was another artist I didn’t know, whose style changed about halfway through his career. Ramsey discusses the possible reasons and implications.

The Hudson River School I had heard of but didn’t realize it was: a group of landscape painters who went into unexplored areas of what would become the United States to show immigrants to the area what beauty and grandeur was there. But the beauty was also untamed and could be dangerous. And the influx of new European plans for colonization would clash with the Native Americans already there whose philosophy about the land was vastly different.

Van Gogh’s infamous cutting off of his ear is told in the context of his trying and failing to establish an artist’s residence with Gauguin. They only lived in the same yellow house for sixty-three days, “two of the most productive month’s of each artist’s career, and two of the most turbulent” (p. 125).

Norman Rockwell’s work was “Dismissed by critics, who considered his paintings to be too idyllic and sentimental to be great art (p. 139). Rockwell agreed his work wasn’t “the highest form of art,” but said “I love to tell stories in pictures–the story is the first thing and the last thing” (p. 139). His work was influenced by the new technology of the four-color press. He became a well-loved fixture of the Saturday Evening Post until he started painting scenes from the Civil Rights movement like The Problem We All Live With and Murder in Mississippi, based on real events.

Edgar Degas is known for detailed paintings of ballerinas, like The Dance Foyer at the Opera in 1872. But macular degeneration slowly changed his work to the much less distinct Two Dancers Resting in 1910. I can’t fathom the difficulty and painfulness of trying to portray one’s vision when one’s vision is deteriorating. After discussing other artists with failing vision, Ramsey notes, “The art changes, but not necessarily in a negative way. Often when affliction and compulsion collide, something deeper, truer, and more lasting is born” (p. 166). He quotes modern artist Jimmy Abegg, who also has macular degeneration, as saying “The bad isn’t so bad when you recognize the goodness that will emerge from it, whatever trail that leads me down” (p. 166). Ramsey comments, “Affliction stirs us awake to things we might not have seen otherwise” (p. 166) and seeing “through new eyes” requires courage and humility.

Ramsey includes appendices on the symbolism often used in art and and famous art heists. One appendix is titled “I Don’t Like Donatello, and You Can Too.” Ramsey says we don’t have to like or “get” every artist, but, with “a posture of openness, willing to learn and grow” (p. 192), we can appreciate even what we don’t like.

A few other quotes that stood out to me:

What comes out of this life is his business, but what I do will never be what makes me who I am. Because this is so, when suffering comes, it doesn’t have the power to unravel God’s design. Instead, the suffering becomes part of the fabric (p. 155).

Our sorrows are ultimately hallowed by the One who enters fully into the painful stories of our own lives in order to show us that our suffering matters, while also becoming the place from which the Spirit enables us to become agents of God’s healing grace to those who find themselves lost and alone in their griefs (p. xi).

The goal of suffering well is to move us not only beyond the stick figures, but also from a place of pride to one of intimacy and familiarity with our Lord. It is to move us not from crude to eloquent, but from unfamiliar to intimate. This is why we practice spiritual disciplines (p. 50).

To truly love someone is to move beyond first impressions into the heart of things; it is to take on the sacred work of stewarding another’s joys and sorrow (p. 132).

Think about the physiology of growing old. If the Lord grants us many years, the way to eternal glory will include the dimming of our vision, the slowing of our bodies, the dulling of our minds, and the diminishing of our appetites. It’s a path that requires us to loosen our grip on this world, preparing us to leave it before we leave it. Is this not mercy? (p. 136).

I had missed the fact that there were discussion guides for each chapter in the back until I finished the book. I wish these had been included at the end of the corresponding chapters.

I don’t know if Ramsey has any future books like these planned. I hope so. There are multitudes more paintings and artists that could be discussed. If he does, I’d love to hear his thoughts on a couple of issues. One, how to think about pictures of deity in art and the second commandment about not making images. I wrestled with my own thoughts on this a few years ago. Two, the depiction of nudity in art. I personally would rather not see nudity in art or anywhere else. (There are a couple of paintings involving female nudity in this book).

As with Ramsey’s first book about art, I appreciated not only the information but the thoughtful and beautiful way the author weaves spiritual truth into the narrative. The result is poignant and meditative.

I know I’d just love this. I’ve loved artwork and classical music for years. I remember being fascinated as a teen when the Indianapolis Symphony came to our small town for a “community concerts” performance with the goal of exposing smaller communities to music. It was such a new and wonderful thing to me! Same with art; just prior to a 3-week European tour with a band just after graduating from high school, we had a few afternoons of college courses on art and architectural appreciation for the things we’d see. I just couldn’t get over all the meaning in artwork. I didn’t know these things existed! Thanks for making me aware of this author.

Outstanding, Barbara — can’t wait to read this book, thanks to your (always insightful) review. And can’t wait to share the quote about the physiology of growing old at the next nursing-home Bible study. Thank you!!! Kitty Foth-Regner 262/263-9122 edgarsfan@aol.com http://www.EverlastingPlace.com Author ofThe Song of Sadie Sparrow It’s never too late to change your tune

Thanks, Kitty! I thought that quote was outstanding. I’m reading a book right now titled Bloom In Your Winter Season by Deborah Malone. I’ve only read the first chapter so far, but it seems pretty good–it might have some good thoughts to share at the nursing home.

Yippee–I’ll look forward to hearing your take on the Malone book! Glad to know that the publishing world is beginning to acknowledge the existence of us Baby Boomers. When my agent originally sent The Song of Sadie Sparrow around to acquisition editors, I believe more than one had a problem with my protagonists being 86 and 58.

I’ve already ordered the Van Gogh title …

I really enjoyed this review! I never really appreciated what art was saying. This has made me think. It’s no wonder that art and music can stir up emotions. Thanks for the review.

Great review, Barbara. I know very little about art, so the info you shared about the artists was all new to me. I was interested in hearing how Norman Rockwell got involved in Civil Rights with his paintings.

The author mentioned his family having a coffee table book featuring Rockwell, and it had no mention of his Civil Rights art work. We had a similar experience with a book about him in our early married years. It’s sad they don’t include that. Then again, he had to work for a different magazine at that time in his life, so maybe the compilers of the books only had permission to use the Saturday Evening Post art.

One of my favorite artist’s stories. We had the huge Van Gogh exhibit here in Chicago at the Art Institute..and the thing that most amazed me was the bare canvas next to layers of paint over a 1/2″ high…and the colors, the spirit laid on canvas. I think I will have to read this book…thanks for the insight. Sandi

Pingback: October Reflections | Stray Thoughts

Hummm, this sounds interesting. Neat.

Thanks bunches for sharing with Bookish Bliss Musings & More Quarterly Link Up.