In the preface to 50 People Every Christian Should Know: Learning From Spiritual Giants of the Faith, author Warren Wiersbe states that he has been greatly helped by reading biographies. “The past is not an anchor to drag us back but a rudder to help guide us into the future.” I love to read biographies as well, and this book included some that were new to me.

In the preface to 50 People Every Christian Should Know: Learning From Spiritual Giants of the Faith, author Warren Wiersbe states that he has been greatly helped by reading biographies. “The past is not an anchor to drag us back but a rudder to help guide us into the future.” I love to read biographies as well, and this book included some that were new to me.

I didn’t realize until I received the book that it was compiled from two former books by Wiersbe, Living With the Giants and Victorious Christians You Should Know, which in turn were originally columns in the magazines Moody Monthly and The Good News Broadcaster, which are no longer being published. I am glad these testimonies have been preserved in this book.

Of the 50 (51, actually: one chapter combines two men), I had previously read biographies of six; I knew something about or had read books by about fifteen others, and the rest were new to me except for just a few whose names I had heard. There are four women, a few missionaries, but most are preachers.

Wiersbe gives a brief history of each person as well as suggestions for books by that person or other biographies of them for further reading. Some of the chapters were a little drier to me than others, but often that occurred when I was trying to read too many of them at one time. The stories I already knew were a good refresher, and some of the others were a good springboard toward finding new biographies to read. Though most of the time Wiersbe tried to convey what the person was like rather than just what they did, there were a couple of chapters where I didn’t get that sense of personality. I did appreciate that the individuals were listed in chronological order, so that we could see the effect of the issues of the day or other people on each person.

A couple of the inclusions confused me, though, as Wiersbe said they “did not preach the atonement”: one, in fact, went from a grace-based faith to a works-based religion. I don’t see how such persons could be considered “giants of the faith,” though Wiersbe did say there were things he learned from them.

One of the overall lessons this books left with me was that God can use anybody. These 51 agreed on most core, fundamental doctrines yet were from various denominations, from opposite sides of the Calvinist/Arminian and other controversies, from differing viewpoints on end times and how ministry should be conducted, from widely different personalities and academic tendencies. and yet God used each one. Does that mean none of those issues matters? No, each individual is responsible to study the issue, the Bible, and in their own conscience before God determine what they believe and how to live it out. But seeing how God used varieties of people helps me to be a little less critical, though I trust no less analytical. We can even learn from the fact that some were gifted in one area but had faults in others, as we are all in the same state.

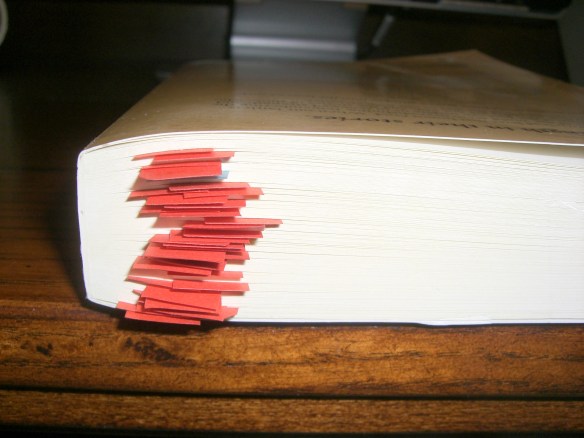

I marked more passages and quotes than I can possibly share in one post…

But here are a few that stood out to me:

Often, after hearing his father preach, Matthew [Henry] would hurry to his room and pray that God would seal the Word and the spiritual impressions made to his heart so that he might not lose them (p. 25).

An excellent exercise. Perhaps that’s part of what made him the commentator he was.

No place is like my study. No company like good books, especially the book of God. ~ Matthew Henry (p. 27).

My endeavor is to bring out of Scripture what is there and not to trust in what I think might be there ~ Charles Simeon (p. 49.)

Amen. Would that all preachers would so do.

“Tried this morning specially to pray against idols in the shape of my books and studies. These encroach upon my direct communion with God, and need to be watched” ~ Andrew Bonar (p. 77).

Books and studies are helpful but even they can take the wrong place in our hearts and minds.

“I can see a man cannot be a faithful minister, until he preaches Christ for Christ’s sake, until he gives up striving to attract people to himself, and seeks only to attract them to Christ” ~ Robert Murray McCheyne (p. 82).

“To efface one’s self is one of a preacher’s first duties. The herald should be lost in the message” ~Alexander Maclaren (p. 109)

Surprisingly, Maclaren was haunted all his life by a sense of failure. Often he suffered ‘stage fright’ before a service, but in the pulpit he was perfectly controlled. He sometimes spoke of each Sunday’s demands as ‘a woe,’ and he was certain that his sermon was not good enough and that the meeting would be a failure” (p. 109).

Though I am not a preacher, I can identify with those feelings. In fact, I have felt that maybe they were an indication I should not be in the ministries I was in, but I guess that’s not always the case. Similarly, John Henry Jowett wrote of his Yale lectures, which I have heard reference to as a great help by more than one preacher:

The lectures are a nightmare to me, and I am glad of getting rid of them this week! (p. 284).

And later,

Preaching that costs nothing accomplishes nothing (p. 284).

We could say that is true of much service, not just preaching. What the Lord uses in our lives may not always be the incidents where we “feel” spiritual or feel like we’re accomplishing something for Him. This next quote is a help:

“All God’s giants have been weak men, who did great things for God because they reckoned on His being with them” ~ J. Hudson Taylor (p. 133).

“Don’t go about the world with your fist doubled up, carrying a theological revolver in the leg of your trousers.” ~ Charles Spurgeon (p. 143).

I’m smiling because this reminds me of my friend from yesterday’s post. On the other hand,

[Alexander] Whyte was so much of an encourager that he forgot that Christians cannot accept every doctrine men preach, though the men may be fine people (p. 169).

“Fathers and brethren,” Whyte cried, “the world of mind does not stand still! And the theological mind will stand still at its peril.” True. but the theological mind must still depend on the inspired Word of God for truth and direction. Once we lose that anchor, we drift (p. 169).

Religious sentiment, if it is worth anything, must be preceded by religious perception. ~ George Matheson on devotional writing (p. 200).

It is urgently needful that the Christian people of our charge should come to understand that they are not a company of invalids, to be wheeled about, or fed by hand, cosseted, nursed, and comforted, the minister being head physician and nurse — but a garrison in an enemy’s country, every soul of which should have some post of duty, at which he should be prepared to make any sacrifice rather than quit it. ~ F. B. Meyer (p. 216).

“Passion does not compensate for ignorance. ” ~ Samuel Chadwick (p. 249).

“We cannot make up for failure in our devotional life by redoubling energy in service.” ~ W. H. Griffith Thomas (p. 264).

“The Bible never yield itself to indolence.” G. Campbell Morgan (p. 278).

“The ‘soul-saving passion’ as an aim must cease and merge into the passion for Christ, revealing itself in holiness in all human relationships” [Oswald Chambers]. In other words, soul winning is not something we do, it is something we are…and we live for souls because we love Christ (pp. 324-325).

The applause of the crowd is not always the approval of the Lord (p. 370).

Christian leaders must realize that if they suffer from shallowness, the malady will spread throughout their entire organization (p. 370).

When a friend told William Whiting Borden that he was “throwing his life away as a missionary,” William calmly replied, “You have never seen heathenism” (p. 342).

Of Borden, who died at the age of 26 after just starting on the mission field:

Why should such a gifted life be cut short?…”A life abandoned to Christ cannot be cut short” ~ Sherwood Day (p. 345).

I think what he means is that that was what God appointed for him — that amount of time, that mission — and he fulfilled it well and God used him — and still does.

There is a very sweet poem written by Francis Ridley Havergal to Fanny Crosby — I don’t think I had realized they were contemporaries:

Dear blind sister over the sea

An English heart goes forth to thee.

We are linked by a cable of faith and song,

Flashing bright sympathy swift along;

One in the East and one in the West,

Singing for Him whom our souls love best,

“Singing for Jesus,” telling His love,

All the way to our home above.

Where the severing sea, with its restless tide,

Never shall hinder, and never divide.

Sister! what will our meeting be,

When our hearts shall sing and our eyes shall see!

The whole poem/hymn is here.

There were some amusing things in the “My how times have changed” department: D. L. Moody “felt that the bicycle, because of its popularity, was the greatest enemy of the Sabbath” (p. 291). I wonder, 100 years from now, what things people will shake their heads at in wonder that we thought “worldly.”

I imagine some of you who read here regularly will be glad to see this one done — it’s been appearing on my Nightstand posts for months. 🙂 It was neither hard nor tedious to read: it’s just best read a bit at a time rather than plowing straight through. With 50 chapters you could easily take one a week and finish it in a year — or one a day and finish it in a couple of months. Either of those or something between would give you a rich variety of people to learn from.

Though there were some names missing I would have liked to have seen here — Jim Elliot, Jonathan and Rosalind Goforth, J. O. Fraser, Henry Ward Beecher, Martyn-Lloyd Jones (he is referred to a few times), J. Oswald Sanders, Isobel Kuhn — I do understand that every author and book has its limits. 🙂 Overall I enjoyed the book very much.

I’ll close with something William Borden wrote in his notebook in college, something that many of these would echo:

“Lord Jesus, I take hands off, as far as my life is concerned. I put Thee on the throne in my heart. Change, cleanse, use me as Thou shalt choose. I take the full power of Thy Holy Spirit. I thank Thee.” Then he added this revealing sentence: “May never know a tithe of the result until Morning” (p. 345).

(This review will also be linked to Semicolon‘s Saturday review of books.)