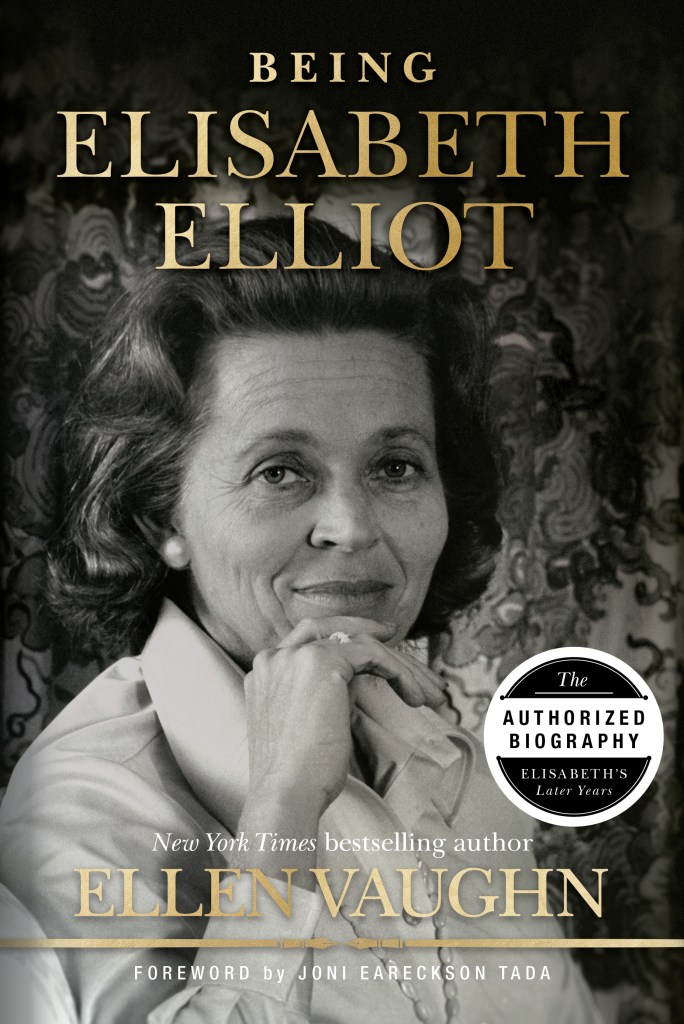

Being Elisabeth Elliot is the second of a two-part biography of Elisabeth by Ellen Vaughn. The first was Becoming Elisabeth Elliot (linked to my review).

I’ve written more about who Elisabeth was in that first review and her influence in my life here, so I won’t go into all that again.

Vaughn’s was the authorized biography: she had access to all Elisabeth’s remaining journals and many letters.

After spending months agonizing over whether to leave or stay in South America, Elisabeth finally felt God would have her go home and be a writer. This volume begins with Elisabeth’s return to the US from Ecuador in 1963 with her young daughter, Valerie.

But then she struggled with what to write, now that she had the time and freedom to.

Plus she was processing much of what had happened in her life so far. Christian literature and missions meetings were filled with victorious tales which she had not experienced. “She railed against the image-conscious habits of the Evangelical Machine, whose every story must end with glorious conversion and coherent happy endings, lest God look bad” (p. 272). She rethought some of her legalistic upbringing. She found that often, God’s ways were inscrutable. He couldn’t be boxed in, figured out, or predicted.

But she found Him trustworthy nonetheless. He may not respond the way we think He should. But He proves Himself good, wise, and holy.

Her private musings during this time period might be shocking and disturbing to some. But I think many of us ask some of the same questions at points in life.

In her first book after the initial ones about her husband, his friends, and their ministry trying to reach the Waorani tribe (then known as Aucas), she wrote a fictionalized account of her experiences in No Graven Image. The book was not well-received. Many misunderstood that the graven image in question was their man-made perceptions of what God should be like.

Vaughn goes on to tell of Elisabeth’s struggles with writing, her widening speaking ministry, her challenges raising Valerie, her surprising second marriage, her husband’s agonizing death from cancer, and her third marriage to Lars Gren. She mentions how some of her books came into being, especially the first few. I would have liked to learn more about the rest of her books.

I was surprised how often Elisabeth said in her journals that she never sought a platform, never wanted to get in the middle of a public debate on thorny issues (especially femininity in a feminist word). But she felt as God gave her openings, she needed to share His truth.

Though she came across as self-assured, she struggled with self-doubt.

I was surprised to learn that she dearly wanted to write a great work of fiction.

From the time Elisabeth Elliot returned to the United States from Ecuador in the early ’60s, she had devoured classic and modern literature that evoked the human condition against the backdrop of God’s mysterious universe. She wanted to write great novels. She wanted to engage and stir urbane New Yorkers. She wanted to call into being essential human truths through the power of story. She wanted pages that she had written to stir people’s hearts in the same way she was so deeply stirred, her heart and eyes lifted up, by well-crafted literature, visual art, and music (p. 253).

She attempted this, but ultimately felt it was beyond her. Many of us are glad God led her as He did, writing nonfiction for Christian women.

Much of what I would have liked to know more about was lost due to Lars burning “most of her journals from the years of their marriage, a choice he now regrets” (p. 274).

I started this book with reticence because I had heard negative things about it. I thought Vaughn’s writing was engaging and readable. I agree that she shared some things from Elisabeth’s journals about her physical relationship with her second husband, Addison, that would have been best left out. I agree, too, that she inserted herself into the narrative more than she should have. Vaughn’s husband died of cancer right after she wrote about Addison Leitch’s death, and having traveled this journey with Elisabeth through her journals was a help to her. But this would have been better placed in an appendix or afterword. Plus she “argues” with Elisabeth in an imaginary conversation as to whether or not she should have married Lars. In various other places, we’re aware of the author in ways we should not have been.

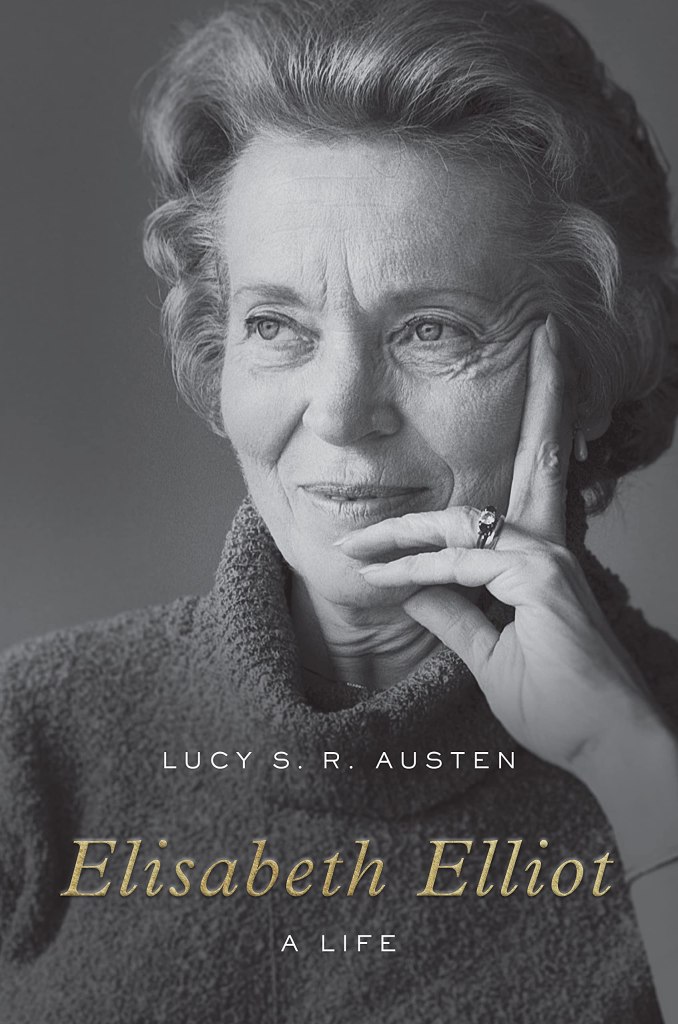

I appreciated Vaughn’s difficulty in trying to tell the truth about Elisabeth as best she could. I can’t imagine filtering through all the material available to her and trying to discern what to share and what to leave out. Though overall she covers the same ground as Lucy S. R. Austen in her biography, they bring out many different things as well.

Elisabeth never claimed to be perfect and would never wanted to have been portrayed as such. She was more complicated than many knew.

The very last page of the book tells about the Elisabeth Elliot Foundation, which is placing all her writings and radio programs in one spot. At the very bottom, the page says the foundation’s mission is to give “Hope in Suffering, Restoration in Conflict, and Joy and Obedience to the Lord Jesus Christ.” I thought this remarkably echoed Elisabeth’s ministry as well.