Augustine of Hippo wrote his Confessions partly as an autobiography, partly to express his views on doctrine.

Augustine was born in 354 and grew up in northern Africa. His mother, Monica, was a Christian, but his father was a pagan until close to his death. Augustine was sent to school to study rhetoric and eventually taught grammar and later rhetoric in Carthage, Milan, and Rome.

In the school he was sent to, boys bragged about their sexual exploits, even making up encounters so as to have something to tell. He began a relationship with a mistress that produced one son. He later agreed to forsake his mistress and marry, but the girl he was engaged to was too young. In the meantime, he took another mistress.

He was involved for many years in Manichaeism and astrology.

When Augustine first began to study the claims of Christianity, he was plagued by what the nature of God was, the origin of evil, and the seeming unconquerable hold his lust had on him.

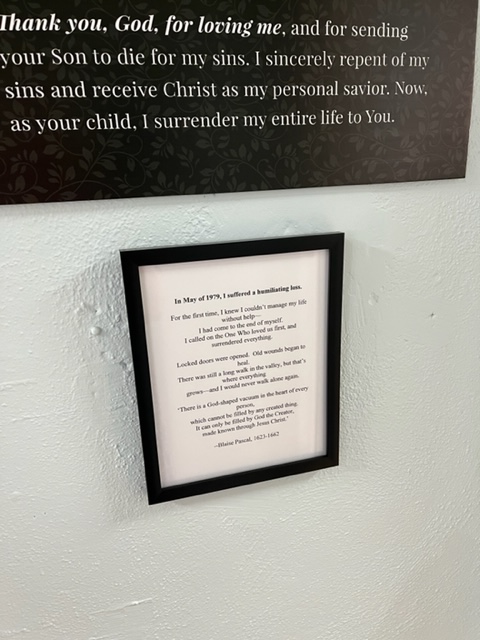

Through reading, study, and conversations with others, he eventually he turned away from Manichaeism, disproved astrology, and came a satisfactory understanding of the nature of God and evil. It took a very long time, however, for him to be willing to give up his lust. He once famously prayed, “Grant me chastity and continence, but not yet.” He tells how this last stronghold was broken and how he came to believe in Christ for salvation and was baptized.

Confessions is written in thirteen books, the first nine autobiographical and the last four philosophical. He was only in his forties when he wrote it and lived until 76, so the book only covers the first half of his life. Wikipedia says Confessions is the “first Western Christian autobiography.” It’s written somewhat like the psalms, with Augustine’s history or thoughts on a subject followed by bursts of penitence or praise. In his introduction, the translator of this edition says:

One does not read far in the Confessions before he recognizes that the term “confess” has a double range of meaning. On the one hand, it obviously refers to the free acknowledgment, before God, of the truth one knows about oneself—and this obviously meant, for Augustine, the “confession of sins.” But, at the same time, and more importantly, confiteri means to acknowledge, to God, the truth one knows about God. To confess, then, is to praise and glorify God; it is an exercise in self-knowledge and true humility in the atmosphere of grace and reconciliation.

Augustine is considered one of the early church fathers. Though a Catholic, he is also claimed by many Protestants as well. Of course, the Reformation wouldn’t happen until the 1500s. But some of the seeds of Protestant thought are in Augustine’s writings, one being the doctrine of original sin.

Confessions was one of those “I probably ought to read that sometime” books. I put it off several times, thinking it would be hard to understand.

The words themselves weren’t hard to understand. The copy I read and listened to was originally translated by Albert C. Outler in 1955 and then included in this version in 2002, so perhaps the archaic language was modernized. But as Outler said in his introduction, “A succinct characterization of Augustine is impossible, not only because his thought is so extraordinarily complex and his expository method so incurably digressive, but also because throughout his entire career there were lively tensions and massive prejudices in his heart and head.” “Incurably digressive” was a good way to put it.

The dialogue and narrative testimony wasn’t hard to understand, either.

But what I found hard to follow were Augustine’s lengthy trains of thought: for example, over 16 Kindle pages pondering what was meant by “The earth was without form and void” in Genesis 1:2, 20 pages on what time is and how it is measured, similar long discourses on memory and many other subjects.

Also, I am not familiar with many of the schools of thought or warring doctrines and philosophies of the times. In fact, I am sorry to say that I know very little about the first millennium AD after the first century or so.

Augustine’s famous quote, “Thou hast made us for thyself and restless is our heart until it comes to rest in thee,” comes from the first page of his confessions. Some of my other favorite quotes:

Thou wast always by me, mercifully angry and flavoring all my unlawful pleasures with bitter discontent, in order that I might seek pleasures free from discontent. But where could I find such pleasure save in thee, O Lord—save in thee, who dost teach us by sorrow, who woundest us to heal us, and dost kill us that we may not die apart from thee.

I especially liked “mercifully angry” and “woundst us to heal us.”

I got a lot from his discussion of the will and struggles with food, especially that “What is sufficient for health is not enough for pleasure.”

He had a section on people with differing interpretations and Scripture and said, “In this discord of true opinions let Truth itself bring concord, and may our God have mercy on us all, that we may use the law rightly to the end of the commandment which is pure love.”

I enjoyed finding an incident I had heard, but did not know came from this book. Augustine’s mother, Monica, had prayed for him for years. She talked to a bishop who had had some of the same struggles as Augustine with the Manicheans. She wanted the bishop to speak to Augustine, but he felt Augustine was unteachable at the moment, and they should just pray for him for now. She cried and begged him, until he said, “It cannot be that the son of these tears should perish.”

There was another illustration I had heard but didn’t realize came from Augustine until I read it here. He tells of a friend, Alypius, who had “a passion for the gladiatorial shows,” but determined they were bad for him and he wouldn’t attend any more. One night he ran into some friends who, with “friendly violence . . . drew him, resisting and objecting vehemently, into the amphitheater” to watch. He determined to keep his eyes closed. But a cry from the audience caused him to open his eyes, and, “as soon as he saw the blood, he drank it in with a savage temper.” He became enamored once again with the violence of the games, receiving “a deeper wound in his soul than the victim.”

There was one famous illustration that I was looking forward to reading that was not in the book. The story is told that, after Augustine’s conversion, he ran into one of his mistresses on the street. He tried to avoid her, but she kept following and calling to him, “Augustine, it is I.” He was said to have answered, “Yes, but it is no longer I.” This article indicates this incident may not have ever happened. On the other hand, it may have come from some of Augustine’s writings that are not searchable online. At any rate, it’s not in his Confessions.

I am not Catholic and therefore couldn’t agree with his distinctly Catholic views. Probably my biggest disagreement is that, though he expressed faith and his life changed before his baptism, he equated salvation with baptism several times in the book. Also, he spends a lot of time near the end of the book interpreting creation allegorically–the firmament is supposed to mean the Bible, the spiritual gifts are supposedly meant by the sun, moon, and stars. etc. He goes into a great deal of explanation as to how he came to these conclusions. But personally, I think we have to be careful not to make something in the Bible symbolic that the Bible doesn’t convey as symbolic. He and his mother also put a lot of stock in visions and dreams, which I don’t.

So, I have mixed views about Augustine. But I am glad to finally have read this book.

I started out listening to the audiobook read by one of my favorite narrators, Simon Vance. I read parts in this 99-cent Kindle version, but didn’t find Augustine’s arguments any easier to follow. The last few pages, I read along while listening to the audiobook. That seemed to be the clearest way for me to gain the most from the book. If I ever read it again—which won’t be for a very long time to come—I’ll have to try it that way from the beginning.

I am counting this book for the Pre-1800 Classic for the Back to the Classics Challenge hosted by Karen at Books and Chocolate.

Have you ever read Augustine’s Confessions? What did you think?