As you’re probably aware, A. A. Milne’s children’s books about Pooh and Christopher Robin and the Enchanted Forest were based on his son, his son’s toys, and the family farm, Cotchford, which edged the Five Hundred Acre Wood (which became the Hundred Acre Wood in the Pooh stories).

Though Christopher Robin was Milne’s son’s name, young Christopher wasn’t called that. He went by Billy Moon, or just Moon (which came from his early attempts to say “Milne”).

A. A. Milne was known for plays and other works when he wrote a few poems and then a couple of books based on Christopher and his real childhood toys. He was dismayed that those books overshadowed all else he wrote. He stopped writing related children’s books because he didn’t feel the extensive fame was good for Christopher.

A few months ago, my husband and I watched Goodbye Christopher Robin, about the Milnes and the fame of Pooh and Christopher Robin. My children had grown up with Pooh (mostly the Disney version) and the Milne characters will always have a soft spot in my heart.

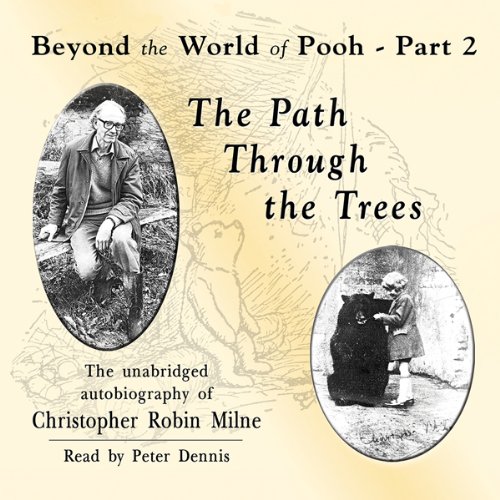

I wanted to learn more about how Christopher (as he was known as an adult) really felt, so I decided to read his book, The Enchanted Places: A Childhood Memoir. I learned shortly thereafter that Christopher had written a sequel titled The Path Through the Trees, so I read that as well, and decided to review them together.

Though there’s a bit of overlap, the first book covers Christopher’s life until he went into the army, and the second covers that time forward. (For convenience sake, I am going to refer to the first as EP and the second as PTT.)

In The Enchanted Places, Christopher tells about his family, his nanny, and growing-up years.

Though the Pooh books were inspired by Christopher Robin’s toys, they also contained his father’s nostalgia about his own childhood.

The Christopher Robin who appears in so many of the poems is not always me. For this was where my name, so totally useless to me personally, came into its own: it was a wonderful name for writing poetry round. So sometimes my father is using it to describe something I did, and sometimes he is borrowing it to describe something he did as a child, and sometimes he is using it to describe something that any child might have done (EP, p. 19).

In the second book, Christopher says that part of his writing the first book had to do with his feelings upon his father’s death. He learned that his mother had destroyed almost everything of his father’s, and at first he was quite angry. Later he came to believe she was right to do so. But he knew that at some point someone would come around wanting to write a biography of A. A., and EP was a place to sort through his remembrances and present “not a full-length study, but just a collection of snapshots” of his father (EP, p. 91). His father “doesn’t wear his heart on his sleeve as [his brothers] do. Alan’s heart is firmly buttoned up inside his jacket and only the merriest hint of it can be seen dancing in is eyes, flickering in the corners of his mouth” (EP, p. 91).

Christopher “quite liked being Christopher Robin and being famous” (EP, p. 81). But in boarding school, “it was now that began the love-hate relationship with my fictional namesake that has continued to this day” (EP, p. 86). The Goodbye Christopher Robin film shows his being bullied at this point, as do a couple of articles I read. He doesn’t specifically say he was in either of these books, but he said the poem “Vespers” “brought me over the years more toe-curling, fist-clenching, lip-biting embarrassment than any other” (p. 23).

Christopher’s lowest point seemed to come after the war when he was looking for a job. He didn’t seem to have any qualifications for anything, a least none that anyone needed. He was a little jealous of his father’s success at his expense then:

But were they entirely his own efforts? Hadn’t I come into it somewhere? In pessimistic moments, when I was trudging London in search of an employer wanting to make use of such talents as I could offer, it seemed to me, almost, that my father had got to where he was by climbing upon my infant shoulders, that he had filched from me my good name and had left me with nothing but the empty fame of being his son.

This was the worst period for me. It was a period when, suitably encouraged, my bitterness would overflow. On one or two occasions it overflowed more publicly that it should have done, so that there seemed to be only one thing to do: to escape from it all, to keep out of the limelight. Sorry, I don’t give interviews. Sorry, I don’t answer letters. It is better to say nothing than to say something I might regret (EP, p. 146).

Christopher says in both books that he was fiercely independent.

However much I wanted to succeed as a bookseller on my own merits, people would inevitably conclude that I was succeeding partly at least on my father’s reputation. They might even think (wrongly) that my father’s money was subsidizing the venture and that–unlike other less fortunate booksellers–I did not really need to make ends meet (EP, p. 148).

In The Path Through the Trees, (sometimes this title is prefaced with Beyond the World of Pooh, Part 2), Christopher tells of his life from the time he began to make his own choices: his five-year stent in the Army, his finishing college, search for a job, marriage, life as a book-seller.

He’s oddly selective about what he writes, which, of course, he has every right to be. He does say this book is “a personal memoir, not a biography” (PTT, Location 3889) and presents “a disjointed story—but a happy life” (Location 31).

In this second book, he tells a great deal about his first love, a woman named Hedda whom he met in Italy. But he tells us very little about his wife, Lesley, except things they did together. She was his cousin, so he had known her for years. But he doesn’t describe her as a person or how they went from cousins to romance. Likewise, he tells us his daughter, Clare, was born with cerebral palsy, couldn’t walk, had limited use of her arms. But he doesn’t describe her personality or appearance. I don’t know if this quietness was for their protection, a result of his own struggles with fame and too much of his life made public, or what.

He spends a lot of time on how they came to be booksellers, how things progressed with the shop, choices they made, things that affected the market, etc. He defends book-selling as a profession—there appears to have been some who regarded book-selling as a “trade” (which was somehow lower in rank than other professions) or as somewhat mercenary.

He has a chapter on animals they took care of (including a vole and owl in their home). In other circumstances, he might have been a naturalist.

He talks a great deal about Dartmouth, the town where he and Lesley settled and had their bookshop.

When Clare was done going to school and came home to stay, she needed full-time care. Christopher stayed home with her while Lesley continued part-time at the bookshop. This seems to have been one of the happiest times of his life, taking Clare out into nature and devising and making various helps for her needs. He had often said that he had inherited his mother’s hands and his father’s brains, and these devices for Clare employed both. His thoughts about equipment for the disabled was interesting:

It is a sad fact that much of the equipment designed for the disabled is inefficient and nearly all of it is ugly. To some extent the one follows from the other. An efficient design has a natural elegance which needs little embellishment to make it attractive. Whereas the wheel chair issued to Clare was such a mechanical disaster that nothing could have redeemed it. How unfair it is that a person who most needs a chair should so often have just the one–and one so very far from beautiful–while the rest of us, who need chairs only now and again, possess so many (PTT, Location 3233).

But of course the greatest pleasure of all was to see Clare sitting comfortably where before she had been uncomfortable, doing something she had not previously been able to do. And it was a pleasant thought that this was, in a sense, a legacy from her grandparents whom she had never known–a product of the fusion of my father’s fondness for mathematics with my mother’s competent hands. If she had inherited neither, she could at least benefit from the fact that I had inherited both (PTT, Location 3243).

Christopher’s independence caused him to refuse accepting money from the Pooh book sales until Clare came home.

Christopher seems to have been a kind and gentle man, though fiercely opinionated on some topics. He was a classic introvert, a thinker. He describes one scene in the second book where he’s walking home and comes upon a couple searching for elephant hawk caterpillars, which they hoped to take back to their area so the bugs would hatch and breed there. Christopher got home and told Lesley about the encounter. Lesley left a few minutes later and came across the same couple. She commented that her husband had just spoken with them. The man replied, shyly, “I thought he looked like the sort of person who would be interested in my caterpillar,” which Christopher took as “a nice compliment” (PTT, Location 3721). I can somewhat picture him ambling around Dartmouth, as he describes it, enjoying his bookshop, stopping to observe and contemplate nature, willing to talk about moths with strangers.

Though Christopher had some rough spots with both parents, and didn’t see his mother the last fifteen years of her life, he loved them and spoke fondly of them in these books.

Sadly, to me, Christopher “converted to humanism” when he was 24, believing that man invented God rather than the other way around. He states this in the first book, but apparently felt he came across a little too strongly. So in the second book he says that though he does not believe in God, someone else can, and they can both be right (which does not make sense, but apparently he means something like “believe whatever works for you and helps you through life”). A. A. was also an atheist but did not push his beliefs on his son until he shared an atheistic book with Christopher in his twenties.

This article tells some of the differences between the film and reality. There are some things in the films that were not in these books but may have come from other sources (A. A. also wrote a biography, It’s Too Late Now, and both Milnes wrote other books as well). Or, as always happens in movies, the makers may have taken a bit of license. One difference this article doesn’t mention is that though A.A. Milne wrote an anti-war book after WWI, he felt war was justified against Hitler and wrote another book telling why. “Hitler was different: different from anything he had imagined possible; that, terrible though war was, peace under Hitler would have been even more terrible” (PTT, Location 140). The film shows A. A.’s battle with PTSD (though it was not called that then). Christopher doesn’t mention his dad having flashbacks or problems adjusting, but he knew he’d had “sad times” in his life and felt they came out through Eeyore.

Another scene in the film comes when young Christopher asks his father, “Are you writing a book? I thought we were just having fun.” Alan responds that he’s writing book and having fun. I think that was accurate: I don’t think A. A. observed his child’s activities with a mercenary air, pulling from them what he thought would “sell.” Perhaps as happens with many parents, having children brings up memories of one’s own childhood, and A. A. recognized what would resonate not only with other children, but other parents.

I read the Kindle version of both books, but then discovered the second was included in my Audible subscription. So the audio and ebook were synced to where I could go back and forth between them. One advantage to listening was hearing the words in an English accent. I knew, of course, Christopher was English, but I don’t think in accents when reading. The audiobook has a lovely postscript not in the books by Peter Dennis, the narrator of this and the Pooh books and a personal friend of the family. I also checked both books out of the library to see if there were any pictures or other material in them. The first book had pictures of Christopher as a child as well as pictures of some of the places in the books side-by-side with the book’s illustrations of those places.

There’s a scene at the end of the film where Christopher tells his father he had more or less made peace with his childhood namesake. In the army, especially, he came across people whose fond childhood memories included Pooh and were a comfort to them. I didn’t read any sentiments like that in these books, but I hope Christopher did come to something like that realization in real life. Though he didn’t want to be mistaken for his fictional namesake, and though he understandably wanted to be permitted to grow up and away from him, the fictional boy and his toys and their innocence and imagination have touched the hearts of children and parents for decades.

(These books fit within the Nonfiction Reading Challenge celebrity category).