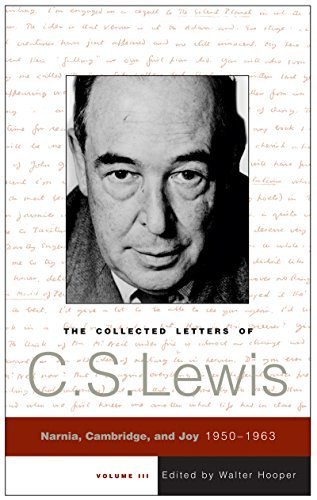

Walter Hooper was an American who became something of a secretary to C. S. Lewis, or Jack, as he was known, in the latter’s final years. After Jack’s death, Hooper helped care for Warnie, Jack’s older brother, and tried to preserve some of Jack’s memorabilia. Many of Jack’s letters had been quoted by Warnie in an earlier book titled Letters of C. S. Lewis, but none is quoted in its entirety. Hooper scoured the various libraries where Jack’s papers were kept to present a comprehensive volume of his letters.

That volume ultimately became three. Volume 1 is titled Family Letters and covers 1905-1931. Volume 2 is titled Books, Broadcasts, and the War, from 1931-1949. The final volume is titled Narnia, Cambridge, and Joy, covering 1950-1963.

I chose to read the last volume first. I had read of Jack’s earlier life in Surprised by Joy and other books, but knew the least about his last several years. This book was a whopping 6,328 pages, so it has taken me a while to read it.

Lewis was a prolific letter-writer, corresponding by hand. Warnie helped him when he was home, then Hooper later. It’s obvious Jack enjoyed a great many of the letters he wrote, but answering correspondence also put pressure on him. He even asked some of his friends not to write in December, because he received so much extra mail then.

One question I had was where these letters came from. Lewis says in this volume that he did not keep copies of the letters he answered once he was done with them. He didn’t appear to use carbon copies. It’s understandable the letters to family members were kept by the recipients. But Hooper doesn’t explain how he obtained the letters written to so many people. I don’t know if he, or Warnie, or someone else put out a request to Jack’s correspondents asking for any of his letters, which were then included in various collections.

Some of the letters are lengthy and thoughtful. Some are short notes. I think some of the short notes about where to meet someone for dinner or when they were coming to visit could have been left out. But even some of these have funny or interesting spots. He writes to lifelong friend Arthur Greeves of their travel plans that since Arthur was a light sleeper and Jack “an unreasonably early riser,” they should ask at the places where they were staying to “be put in rooms not adjacent. (This is not meant as a joke!)”

Some letters were news between friends. Others were answers to questions about his writings or philosophical or spiritual queries. Some gave requested writing advice like that “wh. old Macan gave me long ago ‘Don’t put off writing until you know everything or you’ll be too old to write decently.'”

Some of his letters provided critiques requested by his correspondent of their writing. He didn’t pull any punches! But he was not unkind.

By this time, he refused most of the requests for forewords or prefaces to other people’s books. He just didn’t have time. We forget that, with all his writing, he had a full-time job teaching. He writes to one friend, “I am so busy marking examination papers that I can hardly breath! The very good ones and the very bad ones are no trouble, but the in-between ones takes ages.” Plus, he said to most of these authors that his reputation was such that he didn’t think his name in their books would be a help to them.

I thought it a little odd that no letters to Joy were here. Of course, their main correspondence would have occurred before she moved to England. Perhaps she didn’t bring those letters over, or maybe she or Jack destroyed them. They may have been too personal, concerning her own soul-searching plus problems with her first husband.

It was funny to read how he described her when she visited, though. Evidently she liked to talk a lot. He wrote one friend: “I am completely circumvented by a guest, asked for one week but staying three, who talks from morning till night.” To another he said, “Perpetual conversation is a most exhausting thing.” (I agree!)

Jack said he never appreciated parents before–her two boys were good kids, he said, but whirlwinds that left the “two old bachelors” exhausted by the end of the day.

But he tells through various letters of his developing relationship with Joy, their marriage of convenience so she could remain in England, her illness, a “real” marriage ceremony (the first was legal, but when they began to care for each other, they found a minister who would marry them in her hospital room), her miraculous recovery, and a few good years they had until she began to decline again. He writes near the end of her life, “May it please the Lord that, whatever is His will for the body, the minds of both of us may remain unharmed; that faith unimpaired may strengthen us, contrition soften us and peace make us joyful.”

Jack’s letters are filled with literary references. Hooper painstakingly annotated these, sharing the source, the location within the source, and the full quote Lewis cited.

It’s fun to see humor laced through many of the notes. He asked one friend, “What is a ‘rumpus room’? Rumpus with us means a loud noise, or row, or ‘shindy’. Do you have a special room for shouting in? (I’ve known houses where it wd. be convenient!) To another: “There’s no news at all about Cambridge cats. I never see one. No news and no mews.”

One of the great sorrows of his life was his brother Warnie’s alcoholism. Warnie would go off on benders and then go to a place to dry out, then come home, only to repeat the process later. Jack would let close friends know what was going on, but would tell others that Warnie was sick or in the hospital.

It was sad to read of Jack’s final days, knowing when he was going to die. He was to have one last trip with his friend, Arthur. But they had to cancel due to illness on both their parts. Lewis writes that he is comfortable, “But, oh, Arthur, never to see you again! . . .”

As you can imagine, I have multitudes of quotes highlighted. Here are some that stood out to me:

Of course we differ in temperament. Some (like you–and me) find it more natural to approach God in solitude: but we must go to church as well. Others find it easier to approach Him thro’ the services: but they must practice private prayer & reading as well. For the Church is not a human society of people united by their natural affinities but the Body of Christ in which all members however different (and He rejoices in their differences & by no means wishes to iron them out) must share the common life, complementing and helping and receiving one another precisely by their differences.

God loves us: not because we are lovable but because He is love, not because He needs to receive but because He delights to give.

I am going to be (if I live long enough) one of those men who was a famous writer in his forties and dies unknown–

I don’t wonder that you got fogged in Pilgrim’s Regress. It was my first religious book and I didn’t then know how to make things easy.

[On Queen Elisabeth’s coronation] Over here people did not get that fairy-tale feeling about the coronation. What impressed most who saw it was the fact that the Queen herself appeared to be quite overwhelmed by the sacramental side of it. Hence, in the spectators, a feeling of (one hardly knows how to describe it)–awe–pity–pathos–mystery. The pressing of that huge, heavy crown on that small, young head becomes a sort of symbol of the situation of humanity itself: humanity called by God to be His vice-regent and high priest on earth, yet feeling so inadequate. As if He said ‘In my inexorable love I shall lay upon the dust that you are glories and dangers and responsibilities beyond your understanding.’

How little they know of Christianity who think that the story ends with conversion: novelties we never dreamed of may await us at every turn of the road.

As long as we have the itch of self-regard we shall want the pleasure of self-approval: but the happiest moments are those when we forget our precious selves and have neither, but have everything else (God, our fellow-humans, animals, the garden & the sky) instead.

If only people (including myself: I also have fears) were still brought up with the idea that life is a battle where death and wounds await us at every moment, so that courage is the first and most necessary of virtues, things wd. be easier. As it is, fears are all the harder to combat because they disappoint expectations bred on modern poppycock in which unbroken security is regarded as somehow ‘normal’ and the touch of reality as anomalous.

We should mind humiliation less if [we] were humbler.

I’m so pleased about the Abolition of Man, for it is almost my favourite among my books but in general has been almost totally ignored by the public.

At the end of this volume, Hooper included a series of letters between Lewis and his friend, Owen Barfield, called “the Great War” in which Lewis tries to “dissuade Barfield from his belief in anthroposophy,” a “system of theosophy . . . based on the premise that the human soul can, of its own power, contact the spiritual world.” The timing of these belonged to one of the earlier volumes, but Hooper didn’t receive them until he was working on this one. I didn’t read these, because they were quite long and I couldn’t follow the reasoning. I scanned some of them.

Hooper also includes extensive biographies in the back of Jack’s regular correspondents as well as interesting details about them or their interactions with Jack (which, along with the index, makes up some of the lengthy page count). I did not read all of these, either.

I very much enjoyed reading these letters and getting to know Lewis a little better. Someday I’ll get back to the other two volumes.

(Sharing with Bookish Bliss)